It’s National Organ and Tissue Donation Awareness Week. Talk to your family about your organ and tissue donation wishes.

By Michelle Hampson

Transplanting organs, tissue or stem cells from one person to another saves lives. It was not easy to figure out what facilitates a healthy and successful transplant though. Efforts over a long time reveal the complexity of the procedure and that very specific circumstances are required. As researchers’ understanding of the immune system improved, so did the success rate of transplants.

First recorded kidney transplant from one human to another

In April 1933 in the USSR, a young woman was rushed into a hospital. After ingesting mercuric chloride in an attempt to poison herself, her kidneys were failing.

Kidneys play a vital role in filtering out toxins from the body in the form of urine, and after four days in the hospital the 26-year-old had not passed any urine at all. With severely damaged kidneys, the poison had accumulated in her body, causing pain and convulsions.

By chance she had been admitted to a hospital where a surgeon, Yurii Voronoy, was studying transplantation medicine. He performed the world’s first recorded transplant of a kidney from one human to another. Remarkably, the kidney was able to excrete a small amount of urine after Voronoy attached its blood vessels to a major artery in the patient’s leg – her mercury levels actually dropped. However, after two days the transplant failed, and the young woman died.

Over the next few decades, similar attempts were made by various doctors to save lives, but after a handful of days the transplanted organs were always rejected, meaning the patient’s immune system recognized the new kidney as “foreign” and attacked the donated tissue.

Even when donors and recipients were matched for blood type, transplants sometimes ended in rejection. It wasn’t until the 1950s when it became clear that, in some cases, a kidney can be transplanted from one person to another without rejection, providing the recipient with years of extra life. So why were some kidney transplants successful while other were not?

A major clue came in 1954, when Ronald Herrick donated a kidney for his identical twin brother, Richard. The donated kidney lasted eight years, until Richard died of a heart attack.

A pattern became evident showing that the immune systems of recipients were less likely to reject transplanted tissue if the donor was a sibling. Since then, important research looking more closely at the immune system and how it recognizes tissues that belong in the body (“self”) or tissues that are foreign has been key to dramatically improving the success rate of transplants.

Not all cells are the same

The challenging part is to find organs, tissues or stem cells from a donor that are similar enough in nature to the patient’s to avoid rejection.

While red blood cells are lined with proteins, which doctors use to identify a person’s blood type using the ABO system, there is another set of proteins that must be matched in order for successful transplantation, which applies to all types transplants, be it kidney, blood stem cell or otherwise.

Proteins called human leukocyte antigens (HLAs) line the surface of most cells in our bodies and each person has a rather unique composition of HLAs. These markers are what your immune system uses to identify which cells are “you” and which may be foreign. Each individual inherits one set of HLAs from their mother and one set from their father, so siblings are the most likely to have enough HLAs that match close enough for a transplant, with a one in four chance. Identical twins, such as Ronald and Richard, will be perfectly matched.

There are two main classes of HLAs, or “markers”. In Class I, there are three different subtypes of markers: A, B and C. As for Class II, many different markers exist. But the two most commonly tested when trying to find a donor-recipient match are DR and DQ. These five core types of antigens – multiplied by two because individuals receive one of each kind from their parents – means ten different antigens need to be analyzed and matched when trying to find an appropriate donor. (Read more about it in a recent post on this blog about the development of a web-based application used by the entire Canadian transplant community to estimate the percentage of Canadian organ donors with whom a transplant candidate may be incompatible.)

The reason that it can be so difficult to find a donor-recipient match among strangers is because there are numerous different subtypes of HLAs within each of these groups. For example, there are more than 3,200 class I antigens alone. This means that there are a staggering number of HLA combinations among the human population. Finding a match can be like trying to find a needle in a haystack.

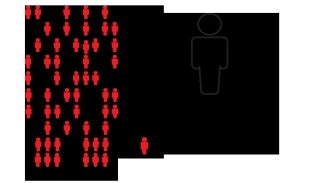

Approximately 4,500 Canadians are waiting for a lifesaving organ transplant and many more are waiting for tissue transplants.

Science has come a long way, from recognizing patterns of successful tissue transplants among siblings, to identifying specific HLA types to find the best possible donor-recipient match and ultimately improve the outcome for the patient. Perhaps the biggest challenge in saving lives now lies less in science, and more in the education, understanding and generosity of donors.

Canadian Blood Services plays an integral role in Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation in Canada by managing clinical programs that support interprovincial sharing of organs: the Kidney Paired Donation Program, a living donation program that looks for compatible transplants created through chains and paired donation from otherwise incompatible pairs, the Highly Sensitized Patient program, a program that improves chances of a kidney transplant for hard to match patients by looking for matches nationally, with support for other high status organ sharing, and the National Organ Waitlist, a real-time data source for non-renal patients throughout Canada.

About the author

Michelle Hampson is a writer who has spent years communicating medical science and treatment options to people living with chronic conditions, such as cancer and autoimmune diseases. Now based in Washington, DC, she reports on research published in the journal Science.

The opinions reflected in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Canadian Blood Services.

Related blog posts

A new innovation by a team of Canadian Blood Services researchers and the National HLA Advisory Committee has improved the situation for Canadian transplant patients. Launched in April 2012, the Canadian cPRA Calculator was developed to support Canadian Blood Services’ transplant programs. It’s a...