Blood transfusions are a lifeline for people living with sickle cell disease

More than 6,000 people across Canada have sickle cell disease, and many rely on blood donors

Sickle cell disease makes the normally pliable, round red blood cells stiff, elongated, and they can get stuck in small blood vessels. The disease can cause organ damage, affects the immune system and increases the risk of bacterial infection.

People with sickle cell disease vary in their need for donated blood. Some receive periodic transfusions. Others need to have their red blood cells fully replaced from healthy donors on a regular basis, through a process called “red cell exchange.”

A person’s detailed blood type is linked to ethnicity, so a person with sickle cell of African ancestry, for example, may rely on donors with a similar ancestry for lifesaving treatment. Canadian Blood Services continually strives to recruit donors from diverse communities to meet the needs of all patients.

Below are stories from five of the estimated 6,000 people across Canada living with sickle cell disease — the most common inherited condition in the country.

The Felix brothers

Two of Nahomie Acelin’s three sons ― Micah Felix and Joiakim Felix ― have sickle cell disease and rely on blood donors for part of their treatment.

“I think donors are incredible,” says Nahomie, who lives in Gatineau, Que., not far from the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario (CHEO) in Ottawa where her sons go for treatment. “Just the fact you take the time out of your day, and you decide to go to a place where they’re going to put a needle into your arm, and it has no benefits to your personal self, I think that’s incredible.”

When she sees the pouches of blood her sons receive, she thinks about those donors she’ll never meet.

“There’s no name to the bag, there’s no face to the bag, but we know that someone decided to wake up in the morning and be a lifesaver for somebody else,” she says.

Nahomie and her family also work to raise awareness of sickle cell disease. Read more about the family’s journey, including her children’s book about sickle cell disease called The Battle of Ottogatz: The Super Felix Brothers.

Ulysse Guerrier

Ulysse Guerrier was born in Toronto in 1976, after his parents immigrated from Haiti in the early 1970s. Four of the family’s five children were diagnosed with sickle cell disease. Two of them have since passed away. At two years old, Ulysse was diagnosed with Sickle Cell S Beta Thalassemia, a type of sickle cell disease that is associated with beta thalassemia, a blood disorder that reduces the production of hemoglobin.

“I got sick when my family was on vacation in Haiti,” Ulysse says. “My parents took me to a doctor who ultimately diagnosed me with sickle cell disease, a disease that is common in Haiti and other Caribbean and African countries.”

After his diagnosis, Ulysse and his family were introduced to various forms of pain management, but the side effects of the drugs have been severe making them an unsustainable option. He has had an average of two units of blood per month since he was ten and currently receives monthly red cell exchanges, where his own red blood cells are replaced with cells from donors.

Because he relies so much on donated blood to treat his disease and to live, Ulysse works hard to increase awareness of the need for more blood donors and in particular, blood donors from Black, African and Caribbean backgrounds.

“It’s very important to have a bigger pool of diverse donors,” Ulysse says. “It’s only when things hit close to home that it becomes important to you. You shouldn’t wait for a tragedy to make the decision to help.”

Biba Tinga and her son, Ismael

Biba Tinga was a young mother living in Niger when she first learned about the importance of a robust blood system. Her seven-month-old son was diagnosed with sickle cell disease (SCD). By the time he was one year old he had already received multiple blood transfusions.

“That's when the head nurse at the hospital said to me that sickle cell disease manifests in different ways. Every single individual has different complications. But we think your son has sickle cell anemia and he's going to need blood for the rest of his life,” Biba recalls. Sickle cell anemia is typically the most severe form of the disease.

Biba, her four children and her husband moved to Canada where one of the first things the doctors did was put her son on a blood transfusion program.

“They told us that he had a three-year growth delay and the only way for them to help him catch up was to put him on a blood transfusion program for an entire year,” Biba says. “He received transfusions every month, regardless of if he had a crisis or not. It was a miracle treatment for him. He grew like a mushroom.”

It was during one of these blood transfusions that Biba came to understand the importance of ethnic diversity in the blood system. Her son, like many other people living with SCD, had a bad reaction to the blood he was being given because it was not a close enough match to his own. People with complex and ongoing transfusion needs have better outcomes when blood comes from a donor who shares the same markers on their red blood cells (known as antigens) — which are inherited. In situations where rare red blood antigens are required, recipients rely heavily on donors who share similar ethnic background. Biba’s son got sick but was able to recover, but for others it can be fatal. Because of her experiences, Biba has become an advocate for those living with sickle cell disease and now leads the Sickle Cell Disease Association of Canada as its president and executive director with the hopes of ensuring that no one in Canada ever has to go through the lack of phenotype blood the way her son did.

“I've always said that I am so very grateful for the many people in Canada who have donated blood for all these years for my son to still be around. Because that's the only thing that is keeping him alive and healthy,” Biba explains. “I'm so grateful. I don't know who they are. But I hope that the message gets to them and that they continue to donate.”

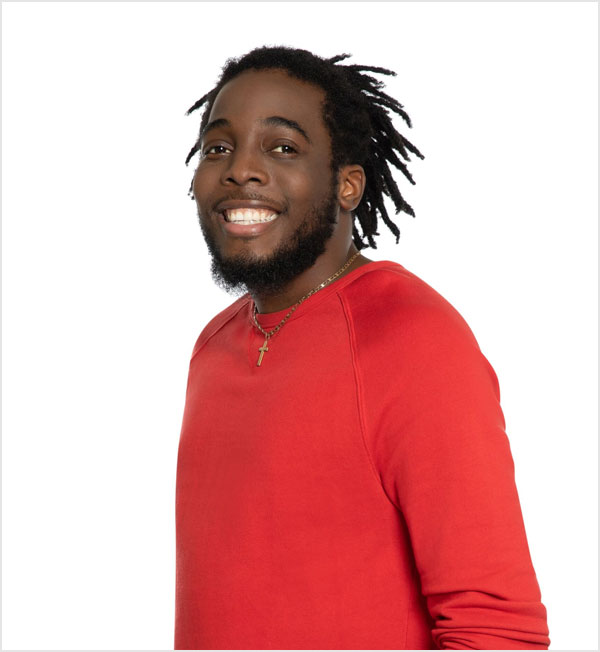

Andy Anyaele

Andy, who is 27 and the eldest of four brothers, was diagnosed with sickle cell disease at one year old.

In the days before his regular blood transfusions, he frequently suffers pain and exhaustion, but the treatments “make it possible for me to live a very normal life,” says Andy. That includes everything from camping trips with friends in Algonquin Park to the simple pleasures of home.

“I can go downstairs, make myself some food, come back up and watch some T.V.,” he says. “It’s just about waking up every day. That’s a blessing.”

While those regular blood transfusions are essential, Andy has also required blood during emergencies. He is filled with gratitude and respect for all those who donate blood. “It’s serious commitment. I appreciate that,” he says. “I literally wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for them.”

Did you know that in Canada, insufficient ethnic diversity in our donor base is one of the biggest challenges we face in supporting people living with sickle cell disease?