Canadian Blood Services’ ongoing efforts to build a more inclusive blood system for African, Caribbean, and Black communities

This document undergoes regular updates. Last update: May 2025

--

Canadian Blood Services’ priority is to ensure that high-quality blood products are available for patients from all backgrounds and communities, by building a donor base that reflects Canadian society, especially in terms of racial and ethnic diversity.

We need more people from Black and other racialized communities to become regular blood donors, to help support people with conditions like sickle cell disease or thalassemia, who may require specially selected blood from donors of a similar ancestry. We recognize, however, that anti-Black racism and other barriers to inclusion exist within our organization and impact many people’s experiences with, and perspectives of, blood donation and Canadian Blood Services.

This resource provides a summary of the work that is being undertaken across Canadian Blood Services to address barriers to inclusion experienced uniquely and/or disproportionately by Black individuals and communities.

--

Over 1.5 million people in Canada identify as being Black*, accounting for 4.3 per cent of the Canadian population. Many of those who are 17 years or older have the potential to improve or save the lives of patients across the country and in their own communities, by joining Canada’s Biological Lifeline.

So why then, is less than 1 per cent of the blood donor base Black*?

The answer to this question is complex and multi-faceted. To begin answering it, it’s important that we first acknowledge the history of systemic racism and anti-Black racism in Canadian institutions.

Through deep reflection and examination of some of our donor screening practices (past and present), along with dedicated research, consultations and ongoing community engagement, we’re continuing to learn how anti-Black racism and other barriers to inclusion exist within our organization.

We recognize that anti-Black racism impacts many of the donors we need to welcome through our doors, the patient communities we serve, and the experiences of employees, volunteers, partners and supporters of Canadian Blood Services.

That is why we have committed to addressing systemic racism and other barriers to inclusion as priority areas of work in our current strategic plan.

Canadian Blood Services is seeking to become an anti-racist organization that ensures culturally appropriate, respectful and welcoming interactions for all individuals and communities that choose to engage with us. To achieve this end state, we’re dedicated to ongoing consultations, collaboration and trust-building work with Black, Indigenous, racialized and other equity-deserving communities.

One of the three priorities of our strategic commitment to sustainability, is to reflect and serve the diversity of Canada. These efforts are essential to fulfilling our goal , to build a donor base that reflects Canada’s population and helps ensure that blood products are available for the people who need them, including those living with sickle cell disease, rare blood types and those in need of stem cell transplants.

|

* Note that the term “Black” is used in this article to refer to individuals from diverse African, Caribbean, and Black communities, including those born in and outside of Canada. |

Jump to:

- 1. Current state of the Black donor base

- 2. Eligibility criteria impacting donation and engagement

- 3. Supporting Black patients with sickle cell disease

- 4. Ongoing initiatives and community engagement

1. Current state of the Black donor base

As of 2025, just under 1 per cent of the whole blood donor base, about 2 per cent of stem cell registrants and 5 per cent of cord blood donors in Canada identify as Black. Meanwhile, Canada’s Black population reached 1.5 million in 2021, accounting for 4.3 per cent of the total population. The Black population continues to grow and is expected to reach more than three million by 2041.

To ensure that Canada’s Biological Lifeline is reflective of our country’s population, especially in terms of racial and ethnic diversity, it is important that more people from Black and other racialized communities become regular donors.

Building a donor base that reflects Canada’s population is essential to ensuring that patients have access to the high-quality blood products they need.

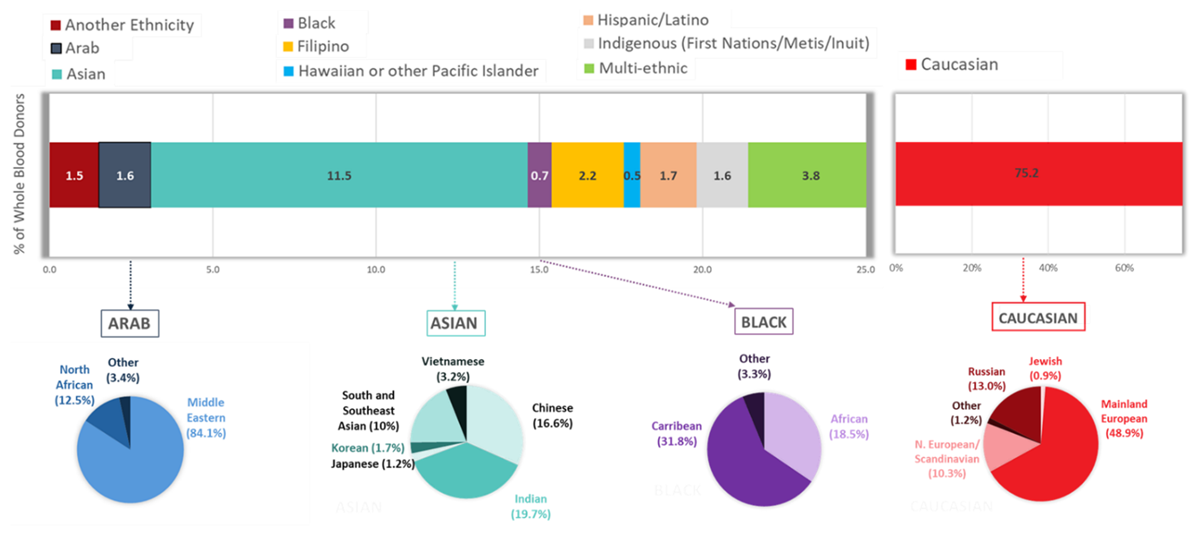

This graph illustrates the composition of our whole blood donor base in 2023, based on self-reported ethnicity. All donors are invited to respond to a voluntary question about their ethnic background. This information helps guide our laboratory teams in performing additional testing for rare blood types that are more common in certain populations. Ninety-four per cent of donors answered this question in 2023.

Note: We are shifting away from gathering data using the term “Caucasian” as it is an outdated racial classification; instead, we use the term “white”. The term “Caucasian” is reflected here, as it was used when asking donors to self-identify in 2023.

Why racial, ethnic and ancestral diversity matter to a blood operator

While most patients can be helped by donors from one of the four main blood types (A, B, AB and O), a small proportion require blood products with more uncommon combinations of blood type markers. These markers exist beyond the usual ABO or Rh blood type systems.

Examples include people with conditions like sickle cell disease or thalassemia, who can have ongoing transfusion needs and may require specially selected blood that may come from donors of a similar ancestry. This is because blood types are inherited.

People in Canada who have sickle cell disease are disproportionately Black, which means donors whose ancestors are from sub-Saharan Africa and/or the Caribbean are more likely to have the blood type combination required to support recipients with complex or uncommon blood type needs.

Blood recipients with sickle cell disease, including those requiring ongoing transfusion support, are less likely to experience side effects if they receive blood products from people with similar blood types.

Additionally, certain blood types are more likely to be found in specific racial groups.

Blood types including the rare U negative, Jsb negative, Joa negative or Hy negative, for example, are only found in people from African, Caribbean, and Black communities. These blood types, or markers on the surface of red blood cells, can influence compatibility in transfusion. While we talk about these blood types less often, they may be very important in ensuring safer transfusion for some patients.

Increasing the size and diversity of our Black blood donor base will, in turn, help ensure that patients requiring specially matched red blood cells have access to the products they need. Learn more about the importance of racial and ethnic diversity in the blood supply.

2. Eligibility criteria impacting donation and engagement

Over the years, and still today, some of our geography-based eligibility criteria have disproportionately impacted people from diverse Black communities, preventing many prospective donors from joining Canada’s Lifeline.

Many of our criteria have undergone necessary changes over time, thanks to advancements in testing platforms, scientific research and understanding of some transmissible diseases, allowing us to submit formal requests for changes to our regulator, Health Canada. However, these changes alone are not enough to remove all barriers to donation.

We have come to understand and are continuing to learn about the ways that some of our policies and eligibility criteria (past and present) impact Black communities. We are prioritizing efforts to address these barriers.

As we continue our efforts to build a more inclusive blood supply system, we know it is important to do so in a way that also acknowledges the past.

That is why we have detailed below, along with information about our ongoing work, some of the historical and contemporary eligibility criteria that continue to have an impact for many people from Black communities.

Historical Africa-related eligibility criteria

In 1996, our predecessor, the Canadian Red Cross, was required by Health Canada to introduce a question to the blood donor screening process that specified eight countries within the continent of Africa (Central African Republic, Cameroon, Chad, Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Niger and Nigeria). Similar questions were introduced at that time in the United States, by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

The question asked potential donors if they had resided in, were born in, and/or had sexual contact with anyone who resided in or was born in one of these eight countries, any time after 1977. If the answer to this question was “yes”, they were not able to donate blood.

At the time that this screening question was introduced, the available testing methods could not reliably detect a new strain of HIV called HIV-O, which was mainly being reported in people from west and central Africa.

When Canadian Blood Services took over responsibility from the Canadian Red Cross Society and began managing the national blood supply system in 1998, this and other donor eligibility requirements were already in place.

Over time, we have been able to obtain Health Canada’s approval to remove the question specifying African countries from our donor screening process.

Below is a brief timeline including the evolution of these criteria:

- 1994: HIV-O was recognized globally and first identified in Cameroon and Gabon.

- 2009: New tests were soon to be licensed in Canada that could detect HIV-O. Canadian Blood Services began extensive discussions with Health Canada, requesting approval to remove the requirement for the questions specifying African countries, in anticipation of these tests.

- 2011: Nucleic acid tests (NAT) to detect HIV-O were licensed in Canada. Tests used in Canada to detect HIV (both the HIV antibody test and the HIV nucleic acid test) are now both licensed to detect HIV-O.

- 2013: Canadian Blood Services received approval from Health Canada to update the question, allowing people from Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Niger and Nigeria to donate blood. Ineligibility to donate remained for those from Cameroon, and a new country, Togo, was added to the question. Health Canada remained concerned about novel HIV strains being reported in these two countries.

- 2016: The waiting period to donate was reduced from an indefinite period to one year, for people who were born in or lived in Cameroon and Togo.

- 2018: Following further discussions with Health Canada, we were able to remove the question entirely from our screening process.

While these historical criteria are no longer in place, their legacy continues to have a lasting impact for many people from Black communities, particularly those who have recently visited or immigrated from Africa.

Additionally, many individuals who were previously impacted by the historical Africa-related screening questions, continue to be ineligible to donate because of a separate set of travel-related criteria related to malaria. However, those criteria are set to change.

More information about these criteria — and our ongoing journey to evolve them — can be found directly below.

Malaria eligibility criteria

Every time someone donates, we ask them where they have previously lived or travelled. This is because the places you’ve been can sometimes expose you to blood-borne infections, such as malaria, that can be transmitted to others through blood transfusions.

Each year, about 6,600 people who book donation appointments are asked to wait three months to donate blood, if they have recently travelled to regions where the chance of acquiring malaria is the greatest.

Another 1,500–2,500 people are asked to wait three years to donate blood, because they have lived for more than six months in a malaria-endemic area, and about 1,000–1,500 people who book donation appointments each year, are informed that they cannot give blood because they have a history of malaria.

The waiting period to donate depends on your length of stay in certain regions. This is because the chance of having a new or previously unrecognized malaria infection diminishes over time, though it can go undetected for many years.

The reason why people with a history of malaria are not eligible to donate whole blood, platelets, or plasma for transfusion, is because the parasites that cause malaria can lie dormant for decades. This means that no matter how much time has passed since someone has recovered from malaria, there remains a small chance they may still carry malaria parasites in their blood.

Because malaria transmission occurs where Anopheles mosquitoes (the mosquitoes that spread malaria) are very active — mostly in regions within sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, Central and South America and Oceania — most people who are unable to donate blood because of our malaria eligibility criteria have either travelled to, lived in, or emigrated from these regions.

This means that longer waiting periods to donate, or ineligibility to donate, disproportionately impact people who are from African, Caribbean or Black communities, East Asian communities, and South Asian communities.

Removing barriers to donation and increasing participation in Canada’s Lifeline for people from malaria-endemic regions is important for those with complex blood product needs, including people living with sickle cell disease and patients requiring a stem cell transplant, who may rely on unrelated donors with similar ancestry.

Below you will find information about the current donor eligibility criteria related to malaria; how we’ve been able to reduce waiting periods for short-term travel to date; and the next steps in our journey, which involve implementing a test for malaria in the donor screening process and changing the current criteria.

Current donor eligibility criteria related to malaria

|

Potential donor |

Eligibility to donate whole blood, platelets or plasma for transfusion |

Eligibility to donate source plasma |

|

If you have spent 24 hours or less in an area of Mexico, Central America, South America or the Caribbean, where the chance of acquiring malaria is the greatest |

Eligible to donate today |

Eligible to donate today |

|

If you have spent less than six months in an area where the chance of acquiring malaria is the greatest |

Eligible to donate three months after the date you left the country/region |

Eligible to donate today |

|

If you have spent more than six consecutive months in an area where the chance of acquiring malaria is the greatest |

Eligible to donate three years after the date you left the country/region |

Eligible to donate today |

|

If you have previously had malaria |

Not eligible to donate |

Eligible to donate six months after date of recovery |

Learn more about malaria and blood donation

We often get asked by individuals and communities impacted by these eligibility criteria, why we don’t just test for active malaria infections in our donor screening process.

In early 2025, Health Canada approved the first molecular test to screen blood donations for malaria. This test was developed by Roche, a healthcare device company that creates innovative medicines and diagnostic tests.

The availability of this test in Canada moves Canadian Blood Services closer to our goal, to introduce selective testing for malaria as part of our donor screening processes and to potentially change associated donor eligibility criteria. We estimate that NAT for malaria will be implemented in our donor screening process by early 2027.

Before we can start using this innovative test, however, we must evaluate how it works within our donation processes, and gain authorization from our regulator, Health Canada, to use it within Canada’s blood system.

Jump below to learn more about the forthcoming donor screening test for malaria.

Evolution of malaria eligibility criteria (1998–2023)

Despite the lack of a Health Canada-approved screening test for malaria, we have been able to make incremental changes to our malaria criteria over the years. Like the historical Africa-related eligibility criteria, the malaria-related eligibility criteria had been put in place by our predecessor, the Canadian Red Cross Society, before Canadian Blood Services was established in 1998.

Over time, we have reviewed these policies and gathered evidence to present to Health Canada, to reduce waiting periods to donate for those who have travelled to malaria-endemic regions for short periods of time.

Since 2022, we have been dedicating significant resources to evaluate potential alternatives to current eligibility criteria.

Below is a brief timeline of the continued evolution of these criteria:

- 2011: Waiting periods to donate were removed for those who recently travelled to Quintana Roo, Mexico and the Dominican Republic.

- 2016: Waiting periods were removed for donors who had spent less than 24 hours in regions in the Americas where chances of acquiring a malaria infection are moderate.

- 2018: Waiting periods were removed for areas requiring mosquito avoidance alone, as per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations. Waiting periods were kept in place for areas where preventative methods (e.g., anti-malarial drugs, topical mosquito repellant or insecticide-treated bed nets) are recommended.

- 2020: Waiting periods for short-term travel to malaria-endemic regions were reduced from 12 months to three months.

- 2022: Canadian Blood Services began a process to review and assess the current eligibility criteria for malaria, using a framework developed by the Alliance of Blood Operators (ABO) that provides blood operators with an approach for making decisions about blood safety.

- 2023: We held formal engagement sessions and conducted interviews with individuals and communities who have been or could be most impacted by eligibility criteria for malaria (e.g., patients, donors, patient organization representatives). We also heard from physicians, researchers and medical professionals with relevant knowledge and experience. During these sessions, we understood from stakeholders that introducing malaria testing during blood donor screening and updating the current criteria for blood and platelets would be a meaningful and impactful change — both for prospective donors and for patients who rely on blood products.

- 2024: Following the assessment of several alternative options, we determined that we would move forward with the evaluation and implementation of selective nucleic acid testing (NAT) for malaria as part of the donor screening process and ultimately, change associated eligibility criteria for blood and platelets. We also published a report detailing our stakeholder engagement process and decision-making approach.

Implementation of nucleic acid testing for malaria (2024–2026)

Nucleic acid testing (NAT) is a method of testing blood currently used by Canadian Blood Services to detect infections such as Hepatitis C, HIV and West Nile Virus in donated blood products.

NAT helps enhance the safety of the blood supply by detecting pathogens which can cause infections or diseases. This type of testing differs from the antibody tests we use to screen blood donations for past infections. You may have specific antibodies in your blood, for example, if you have been previously exposed to certain pathogens, as your body makes antibodies to fight pathogens.

While antibody tests look for signs of past infections, pathogen or antigen tests like NAT can detect active infections. This means that a NAT for malaria would be able to determine if a prospective donor has any infectious malaria pathogens in their blood at the time of donation.

In early 2025, Health Canada approved the first molecular test to screen blood donations for malaria. This test was developed by Roche, a healthcare device company that creates innovative medicines and diagnostic tests.

The availability of this test in Canada moves Canadian Blood Services closer to our goal, to introduce selective testing for malaria as part of our donor screening processes and to potentially change associated donor eligibility criteria.

Before we can start using this innovative test, however, we must evaluate how it works within our donation processes, and gain authorization from our regulator, Health Canada, to use it within Canada’s blood system.

Given that many prospective donors are affected each year by the waiting periods for short-term travel to malaria-endemic regions, we anticipate that introducing NAT for malaria in the donor screening process — and hopefully, eliminating the waiting period for many — will have a positive impact for both donors and patients.

A NAT for malaria will help further safeguard the blood supply; resulting in more people from Black and South Asian communities in Canada becoming eligible to donate. This will help ensure patients with complex and ongoing transfusion requirements have access to the blood products they need.

The work to implement a NAT for malaria is ongoing and is being prioritized.

As of 2025, active and upcoming work involves:

- Collaborating with international, leading developers of testing assays

- Obtaining testing equipment

- Validating tests and gathering data in a Canadian context

- Undertaking a regulatory process (including a submission to Health Canada to request approval to implement this test in our screening process and change criteria)

- Training staff to perform the test

- Developing a clear and respectful process for informing people of unusual test results

We estimate that NAT for malaria will be implemented in our donor screening process by early 2027.

In the meantime, as we strive to implement a NAT for malaria as quickly as possible, we are undertaking significant work to ensure we continue to meet the needs of patients with complex and ongoing needs.

More information about our ongoing work to meet the needs of people living with sickle cell disease, specifically, can be found below.

Minimum hemoglobin requirements

Aside from geography-based eligibility criteria, our minimum hemoglobin requirement is one of the most frequently cited barriers to donation by people from Black communities.

When people donate blood, their body’s iron levels also decrease. Eventually, low iron levels can lead to low hemoglobin/blood count (anemia). People with anemia, as well as those who do not meet the minimum hemoglobin requirements are not able to donate blood.

These requirements can change with age and changes in body functions, and donors of all ethnicities and ancestries can experience low iron levels.

Normal hemoglobin levels may be slightly lower in people who are Black, compared to other groups. Donors and non-donors who are Black have described a general awareness that many cannot donate because of minimum hemoglobin requirements.

Some have indicated they view the criteria as exclusionary and as disproportionately affecting Black people’s ability to donate blood.

3. Supporting Black patients with sickle cell disease

Sickle cell disease is one of the most common inherited red blood cell disorders. Typically, this condition is more prevalent among those whose ancestors are from Africa, the Caribbean, Central and South America, the Middle East and South Asian — however, sickle cell disease can impact anyone, from any racial or ethnic group.

An estimated 6,000 people across Canada are currently living with sickle cell disease, and that number is growing, with continued immigration trends, new births in Canada from parents who carry the sickle cell disease trait and improving care and treatment options resulting in increased life expectancy.

The prevalence of this condition is of great relevance and importance to Canadian Blood Services, given that in Canada, blood transfusion is one of the main treatments available to people living with sickle cell disease.

Transfused blood can be used to treat various health problems caused by sickle cell disease. Sometimes, only a single transfusion is needed. For others, red cell exchanges (where a patient’s “sickled” red blood cells are removed and replaced with a donor’s red blood cells) are required every four to six weeks, for life.

While donors of all backgrounds are needed to support patients with sickle cell disease, people whose ancestors are from sub-Saharan Africa and/or the Caribbean are more likely to have the blood type combination needed for those requiring blood transfusions. This is because blood types are inherited, and people in Canada who have sickle cell disease are disproportionately Black.

Blood recipients with sickle cell disease, including those requiring ongoing transfusion support, are less likely to experience side effects if they receive blood products from people with similar blood types.

Learn more about sickle cell disease and blood donation and explore our FAQs.

Canadian Blood Services is focused on advancing and bolstering initiatives to ensure that patients with complex transfusion requirements have access to the blood products they need.

This work includes:

- Understanding the ethnic composition of our donor base

During the blood donation process, we ask a voluntary question about donors’ ethnicity. This question was first introduced in 2016 and has since helped us to identify and order additional testing of blood products from donors who may have a greater likelihood of rare blood types or antigen combinations.

Patients with rare blood, and with complex or ongoing transfusion needs will often find the most suitable blood or stem cell match from donors of the same or similar ethnicity or ancestry.

- Conducting phenotyping and genotyping of donated blood

Donors who answer the voluntary question about their ethnicity during the screening process, may have a sample of their donated blood sent for further analysis, to determine if they have a rare blood type. This process of “phenotyping” and “genotyping” donor samples is yielding results that have great benefits to patients with complex and ongoing transfusion needs.

For example, by phenotyping (determining blood types directly on red cells) and genotyping (determining blood types through targeted analysis of red cell genetics) donors who self-identify as Black, we’ve been able to type over 53 per cent of these donors for CEK antigen-matched red cells, which are the most important antigens to match for people living with sickle cell disease.

An additional 38 per cent of donors have been typed for the next two important antigens for sickle cell disease, Duffy and Kidd.

We currently prioritize this additional testing for donors who self-identify as having African or Caribbean ancestry.

While we hope to one day have the ability and resources to phenotype and genotype every donation, we prioritize testing for African and Caribbean donors, since they are more likely to have the blood type combination required for patients with sickle cell disease.

With 95 per cent of donors voluntarily self-identifying during the screening process, we’ve been able to increase our ability, since 2016, to provide optimally matched products to recipients.

- Proactively managing our inventory

Our increasing ability to identify and genotype more donors, particularly donors who self-identify as Black, allows us to test, identify and set aside red blood cell units with uncommon and rare blood types for patients with complex transfusion needs, including those with sickle cell disease. We earmark these products so that they may be readily available for patients whenever, and wherever in Canada, they are needed.

Through our rare blood program, we are also able to import specially matched products from international blood operators to Canada, if and when necessary.

We are continuing to undertake and prioritize work to improve services for patients with sickle cell disease who require access to blood products. We are actively working on a project to improve understanding of supply and demand of specially-matched products and identify a dedicated donor base for sickle cell disease patients. This should enhance our ability to forecast and meet demands and develop strategies for targeted engagement and recruitment of donors. As part of this work, we are also working to improve the way that hospitals can order specialized and specially-matched products and keep track of transfusion schedules.

- Developing an organizational sickle cell disease strategy

Given the ongoing and growing importance of optimally-matched blood products for patients living with sickle cell disease, we are developing an organizational strategy to support patients with sickle cell disease.

This strategy will guide our efforts and initiatives for the coming years, as we seek to improve platforms, processes, services and systems, to ensure optimally-matched products are available to patients who need them, without delay. An important focus of this work involves continued engagement and collaboration with health-care professionals who specialize in treating sickle cell disease.

Canadian Blood Services also supports Bill S-280 (an Act respecting a national framework on sickle cell disease), especially the call for a patient registry to support transfusion medicine for patients living with the disease.

Learn more about how Canadian Blood Services supports patients with sickle cell disease.

4. Ongoing initiatives and community engagement

Canadian Blood Services is committed to addressing systemic racism and other barriers to inclusion for Black donors to, in turn, ensure that products are available for patients with complex transfusion needs.

We’re hard at work advancing and prioritizing initiatives to evolve eligibility criteria and improve services for patients with sickle cell disease, for example. However, we know that it’s not enough to remove process or policy-based barriers to donation and expect communities to begin engaging with us.

We also know we can’t do this work alone, which is why we’ve committed, in our current strategic plan, to prioritize trust and relationship-building, collaboration and co-development of strategies and approaches with impacted communities.

We are striving to become an anti-racist and inclusive organization and establish culturally appropriate policies, procedures and practices in consultation with Black communities across Canada.

We don’t just need people from Black communities to join Canada’s Biological Lifeline — we need to ensure that their experiences and interactions with our organization are always positive and respectful, and that they feel represented, valued and that they belong.

Our ongoing trust-building, relationship repair, collaboration and engagement efforts to date (as of early 2025) include:

- Engaging with an external consultant to conduct an audit and analysis of our organization’s policies and practices. This review is being conducted with an anti-Black racism and inclusion lens and is seeking to identify patterns and trends of exclusion impacting Black donors.

- Conducting community-based social science research with Black and African communities to understand barriers and enablers to donation and action research findings.

- Conducting research with over 900 donors and prospective donors from Black and South Asian communities, to help guide our approach to recruiting and engaging donors.

- Engaging and partnering with Black and sickle cell community leaders, organizations and influencers to address donation barriers.

- Attending Black health fairs, meeting with African community associations, attending sickle cell community events and more, to build relationships and deepen understanding of Black community experiences with Canadian Blood Services.

- Growing, supporting, and providing designated funding to our Black, Indigenous and People of Colour (BIPOC) employee resource group, to strengthen relationships with and amongst BIPOC employees and ensure Black perspectives and lived experiences inform initiatives to promote Black inclusion and address anti-Black racism.

- Launching a series of web pages and content dedicated to highlighting the importance of an ethnically diverse donor base, developed in collaboration with Black and South Asian community members and donors.

- Taking steps to establish an African, Caribbean, and Black (ACB) external advisory committee, to help inform and guide efforts to build trust, improve relationships and meaningfully engage with Black communities in Canada. This committee will be formally stood up in 2025.

- Developing a new approach to engaging Black communities and sickle cell communities, working with an organization founded and led by racialized women and women of colour, and engaging in consultation with community.

- Providing training to key decision-makers about how to recognize and correct unconscious and implicit bias.

The above measures will not solve all complex and longstanding issues experienced by Black individuals and communities when engaging with our organization, but we see them as a start.

We’re dedicated to ongoing work and dialogue with diverse communities across Canada and will continue to listen, learn from, and collectively chart a course forward, together, to ensure patients of all backgrounds and identities receive the best possible treatment and care.

About Canadian Blood Services

Established in 1998, Canadian Blood Services is an independent registered charity. We receive most of our financial support from the governments of all provinces and territories except Quebec. Canadian Blood Services operates with a national scope, infrastructure and governance that make it unique within Canadian healthcare. In the domain of blood, plasma and stem cells, we provide products and services for patients on behalf of all provincial and territorial governments except Québec. The national transplant registry for interprovincial organ sharing and related programs reaches into all provinces and territories, as a biological lifeline for Canadians.

For more information, please contact:

TEL. 1-877-709-7773

EMAIL media@blood.ca